Sunday, April 23, 2006

"Crash" - my last comments, I swear...

From my new column at www.411mania.com/movies, titled "The Critic's Critic"...

From my new column at www.411mania.com/movies, titled "The Critic's Critic"...This column is devoted to movie critics - and skewering them for writing what I feel are off-base, misguided or entirely idiotic opinions of films past and present. While I will attempt to remain committed to logical argument and avoid infantile name-calling, I must caution you - some critics really deserve it.

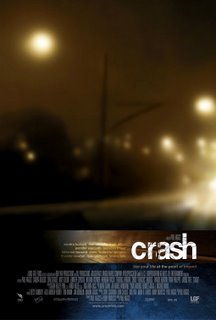

Perhaps the most fitting first target of this column is the king of kings amongst mainstream film critics, Roger Ebert, and his review of the 2005 Best Picture Oscar winner, Crash. Like many critics, Ebert overwhelmingly loved Crash and awarded it four stars in his May 5, 2005 review.

To summarize, Ebert lauds the film’s suggestion that racial conflict will inevitably produce progress towards a more harmonious multi-cultural existence. Decent enough message, I agree, although I feel the film’s success at projecting that message was greatly compromised by writer/director Paul Haggis’ blunt-as-a-medieval-anvil storytelling. Therefore I feel Ebert’s praise is largely undeserved.

Ebert begins his review by summarizing the film’s plot, in my opinion structured as MTV-meets-Shortcuts, before adding the first observation that prompts me to choke on my Chinese food:

Haggis writes with such directness and such a good ear for everyday speech that the characters seem real and plausible after only a few words.

Directness? Yes. Real and plausible? Not even close, precisely because the dialogue is too direct. The racial slurs arrive with the force and frequency of a gatling gun, almost reaching hyperbolic levels with Sandra Bullock as the wife of Brendan Fraser’s district attorney. Her heavy-handed opening salvo of racist dialogue was an immediate blow to the film’s believability.

She screams of a Hispanic locksmith working in her home, “Tell them next time we’d appreciate it if you didn’t send a gang member…the guy in there with the shaved head, the pants around his ass, the prison tattoos…and he’s not going to sell our keys to one of his gangbanger friends? Your amigo in there is going to sell our key to one of his homies.”

Now on to Don Cheadle’s character, who wonderfully sustains the film’s detachment from reality by calling his Hispanic girlfriend a Mexican. She responds, “My father's from Puerto Rico. My mother's from El Salvador. Neither one of those is Mexico,” and he then replies, “Well then I guess the big mystery is, who gathered all those remarkably different cultures together and taught them all how to park their cars on their lawns?” Must every character in this film take every opportunity available to spit out any racial stereotype or slur that comes to mind? Is that how contemporary middle- and upper-class Los Angeles really functions?

At these moments I didn’t feel like I was watching characters existing in the same world as me. Rather, Crash plays like the ham-fisted result of a screenwriter who’s too afraid of being subtle because he’s too cynical towards what he apparently feels is an oblivious audience - one that won’t understand after the first fifty racial slurs that his movie is about - yes, racism.

Next on Ebert’s review:

For me, the strongest performance is by Matt Dillon, as the racist cop in anguish over his father. He makes an unnecessary traffic stop when he thinks he sees the black TV director and his light-skinned wife doing something they really shouldn't be doing at the same time they're driving. True enough, but he wouldn't have stopped a black couple or a white couple. He humiliates the woman with an invasive body search, while her husband is forced to stand by powerless, because the cops have the guns -- Dillon, and also an unseasoned rookie (Ryan Phillippe), who hates what he's seeing but has to back up his partner. That traffic stop shows Dillon's cop as vile and hateful.

But later we see him trying to care for his sick father, and we understand why he explodes at the HMO worker (whose race is only an excuse for his anger). He victimizes others by exercising his power, and is impotent when it comes to helping his father. Then the plot turns ironically on itself, and both of the cops find themselves, in very different ways, saving the lives of the very same TV director and his wife. Is this just manipulative storytelling? It didn't feel that way to me, because it serves a deeper purpose than mere irony: Haggis is telling parables, in which the characters learn the lessons they have earned by their behavior.

Here Ebert actually gets it somewhat right where other critics and viewers fail. He realizes that Dillon saving Thandie Newton - the same woman he molested on the side of the street - from a car crash is not senseless irony yet not a clean-sweeping act of moral redemption either. But Ebert seems to buy into Haggis’ suggestion that because Dillon has a crummy home situation we should at least reconcile his vile behavior towards Newton. However, the moral scales just don’t balance. It takes much more than deep-seated frustration with your home life to act with that kind of cruelty towards a complete stranger AND her husband. In this respect I couldn’t help perceiving Dillon as anything more than an inherent monster aggravated by circumstance. And saving Newton from the crash? It’s his job and people were watching. Any genuine interest he had in saving her life felt entirely undeserved after the malice he showed forcibly finger-banging her roadside. If Haggis did desire to depict Dillon as Ebert interpreted - someone who overcompensates outside the home for the powerlessness he feels there - then the writer/director chose a sickeningly heavy-handed way of doing it. Furthermore, if Dillon’s character was truly a decent man he wouldn’t have intimidated his partner into keeping his mouth shut about the incident. Next:

(Crash) shows the way we all leap to conclusions based on race -- yes, all of us, of all races, and however fair-minded we may try to be -- and we pay a price for that. If there is hope in the story, it comes because as the characters crash into one another, they learn things, mostly about themselves. Almost all of them are still alive at the end, and are better people because of what has happened to them. Not happier, not calmer, not even wiser, but better. Then there are those few who kill or get killed; racism has tragedy built in.

The ham-fisted poetic nonsense of “crashing into each other” aside, Ebert once again fails to truly engage the film. Did the characters really earn their emergence from its - oh, I’ll buy into it - wreckage as truly better people? The transformation of Sandra Bullock’s character comes about with so meager an impetus that in her story, the film continues to abandon any attachment to reality. No one is that damn fickle. So yes, she is an undeservedly better person by the end of the movie.

For Matt Dillon’s reprehensible character, saving a life as a consequence of doing his job is perhaps one degree of moral improvement - about as significant as a one degree rise in Antarctica’s temperature. And Dillon’s partner, played by Phillippe, probably emerges from the film the worst off. If he had truly been “bettered” by his experiences with his partner and Terrence Howard’s character, he wouldn’t have acted so coldly towards his African-American hitchhiker or blown him away out of baseless suspicion. Oh, but there was a base of suspicion - a stereotype of black people as gun-toting, cold-blooded killers. When he discovers that his passenger was reaching not for a gun but a guardian angel medallion similar to the one he carries in his car, Phillippe’s character doesn’t learn from or atone for his tragic misjudgment. Instead, he hides the body and fails to own up to his crime. Real moral improvement there.

Ebert concludes:

Not many films have the possibility of making their audiences better people. I don't expect “Crash” to work any miracles, but I believe anyone seeing it is likely to be moved to have a little more sympathy for people not like themselves. “Crash” is a film about progress.

No, “Crash” is a film about hopeless stagnation. The film is more a circle than a straight line - or even a zigzagged one that ultimately ends up ahead of its beginning point. It’s a hyperkinetic cross-section of multi-directional racism in contemporary Los Angeles with vogue photography marked by an oversaturated color key. It fails to say anything about the issue of prejudice except for brilliantly pointing out that we’re all subject to it. Well of course we are - it’s human nature and evolutionary. If I wasn’t prejudiced in some way, I’d have no qualms about walking down dark and smoky alleys at night or opening the bank door for men in ski masks. Although this message is indeed lost on people sometimes, Haggis is too busy with his sledgehammer-strength manner of storytelling to express it with any artistic subtlety. No, Paul, really - there were BLANKS in the gun? No f’n way!

As for Ebert’s remark that the film will move viewers “to have a little more sympathy for people not like themselves” - if anything, Crash inspires less. The film’s caricatured depiction of the racist and prejudiced invites much more scorn towards those people than sympathy for their targets. In other words, Crash breeds intolerance for the intolerant. Even Roger Ebert fails to crash into this truth.

(photo courtesy of www.hollywoodjesus.com)

I will never tire of Crash-bashing.

And I thought I was good looking.

Post a Comment

Wilcox vox. | Blogger Templates by Gecko &

Fly

No part of the content or the blog may be reproduced without permission.